Spine

Select a treatment from the list below.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

Indication for Epidural

An epidural of steroid is given to reduce the inflammation in the lower back. It is both used to help you with your pain but also can be useful for the surgeon/pain doctor to establish the cause of back or leg symptoms. It is generally given to treat a disc prolapse, pinching of the nerves, called stenosis or disc degeneration.

Procedure

It is a day case procedure, where you will be admitted onto a ward, consented by the doctor and will discuss the procedure with the anaesthetist, who will usually give you some sedation to make it as comfortable during the epidural as possible i.e. you will be very sleepy and unaware of the epidural procedure. The needle is placed at the base of the spine, dye to used to ensure correct position and the epidural is given.You may experience some leg or groin numbness for 12-24hours after the procedure, which can be entirely normal.

Risks

Infection – There is a very small risk of infection due to puncture of the skin

Haematoma – A blood clot causing nerve irritation is very rare but we shall therefore advise you about certain medications (Clopidogrel, Warfarin)

Bladder retention – Sometimes the local anaesthetic can numb the nerves to the bladder and stop usual function. This is rare but sometimes requires a catheter to be inserted

Nerve damage – A very rare complication

Headache – Sometimes the canal that lines the spinal cord and brain can be punctured and this can lead to a headache, which will settle after a few hours/days.

Follow-Up

You shall be followed up in clinic about 4-6 weeks after the epidural to establish the benefit. It is important you keep a mental note of the benefit from the injection so this can be relayed in clinic.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

These can be lumbar, thoracic, or cervical and can be central or foraminal. These are more specific than the caudal epidural. X-rays are used to guide the needle precisely. Normally sedation is required to allow this to happen.

Because these injections are near to the spinal cord or the end of the spinal cord (the cauda equina) much more care has to be taken in placing the needle to avoid damage to those structures and blood vessels nearby.

This means using x-rays is essential. Females of child bearing age should inform the treating doctor if there any chance they might be pregnant.

Side effects can be temporary leg numbness due to the local anaesthetic, there is a very low chance of infection or an injection into the spinal cord itself, causing prolonged numbness of one or two days.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

The facet joints are small joints between vertebral bodies which extend from the base of the skull to the lowest joint between the 5th lumbar vertebral body and the sacrum. An identical joint, in a different plane exists on each side in a mirror image fashion. The joints of the spine are designed to allow movement of the spine in a number of different planes and are separated by a lubricated membrane, the synovial membrane which allows the joint surfaces to glide over one another.

With advancing age wear and tear occurs in the facet joints resulting in loss of the joint lubrication, contact between bony surfaces and the triggering of pain. Pain from a lumbar facet joint can trigger secondary muscle spasm resulting in stiffness associated with pain. Classically therefore the patient with worn facet joints who becomes symptomatic will complain of stiffness in the lumbar area which is particularly pronounced in the mornings and often only relieved by mobilisation or a hot bath. Typically, the pain is present in the lumbar region but may be referred to the legs particularly the buttock area and the posterior area of the thighs.

This pain referral to the legs is not defined as sciatica. Sciatica itself is defined as pain which is perceived distal to the knees and is usually indicative of a different cause such as a prolapsed intervertebral disc or piriformis syndrome. Movements which extend the spine backwards usually result in an exacerbation of the pain and this form of pain is particularly prominent during prolonged periods of standing or sitting.

The technique of lumbar facet joint injection

At Joint Reaction lumbar facet joint injections are performed on a day case basis under sedation to ensure the maximum comfort of the patient and utilising x-ray control to ensure optimal placement of the injection treatment. Injection may take place into the joint itself employing local anaesthetic and steroid combinations or alternatively the nerve supplying painful sensations (and only painful sensations) to the joint may be blocked either on a temporary basis using a local anaesthetic or more permanently employing a technique called radiofrequency lesioning. The latter technique is more complex and employs cutting edge technology but associated with a slightly higher risk of complication.

As mentioned above the injections are accomplished under x-ray control and with the benefit of sedation. After injections patients are usually discharged from the hospital within approximately 4 hours. At Joint Reaction we generally advise patients to take one to two days leave from employment as not infrequently there is a short term exacerbation of pain prior to the commencement of improvement. The onset of improvement is often several weeks post injection as usually a long acting steroid is employed which pharmacologically has a slower onset of action. The maximum benefit from this treatment usually occurs after approximately 10 – 12 weeks post injection and the best results are obtained if injection is combined with post injection physiotherapy, chiropractic or osteopathic treatment.

If you are receiving anticoagulant therapy such as Warfarin, have a known allergy to local anaesthetics, are pregnant or have local or systemic infection it is inadvisable to undergo facet joint injection. If you are concerned about matters such as this, it is advisable to discuss these matters with your specialist prior to consideration of facet joint injections.

The purpose of facet joint injections is to render the patient increasingly mobile with decreased levels of pain. Statistically approximately 70% of patients will derive a reduction in their pain levels of at least 50%. Risk factors are absolutely minimal. The quoted figures for nerve injury are of the order of 1 in 10,000 and other complications are of a minor degree including a brief exacerbation of pain, bruising or pain at the site of injection.

Performed by – Sarmad Kazzaz

There is a different therapeutic modality (form of treatment) for the management of more chronic facet joint pain. If intra-articular injections are of benefit but only on a temporary basis then an alternative means of reducing pain transmission of the facet joints is to block, stun, freeze or burn the small nerves which carry pain messages from the facet joints to the brain. This can be done locally in the spine by injection techniques and does not require any form of surgical incision.

It is important to realise that this process which is called denervation only interferes with the transmission of pain impulses from the facet joint as the small nerves which supply the pain messages only carry pain sensations. They do not carry impulses required to make muscles contract nor do they supply sensation in other vital organs such as the bladder or bowel.

Interrupting these nerves pathways by the technique of denervation is often very effective giving patients significant pain relief (i.e. defined as greater than 50% pain reduction) in about 2/3rd of patients.

It is associated with very few potential side effects if accomplished under x-ray control and can be considered the treatment of choice short of surgery. If the nerves are “stunned” then most patients will experience between 10 and 12 months benefit and this may be prolonged by burning the nerves. Burning the nerves is not always the treatment of choice in the initial stages as although it is associated with prolonged benefit (averaging 2.5 years) there is a slightly enhanced risk.

Performed by – Sarmad Kazzaz

History

Botulinum Toxin (in its most common preparation commonly know as Botox) has a fascinating history. The toxin itself which derives from the bacteria Clostridium Botulinum (not to be confused with the agent responsible for severe diarrhoea known as Clostridium difficile) was associated with the bacterium as early as 1895. Subsequently the toxin itself was isolated by Dr Sommer at the University of California in 1920s. In 1940s Edward Schantz purified the toxin and persuaded colleagues to investigate its physiological action.

The agent was first used clinically by an ophthalmologist Dr Scott to correct hyperactivity in eye muscles in the condition known as strabismus.

In 1988 the American Company Allergan based in Irvine California obtained the right to conduct clinical trials into the drug’s efficacy for indications such as cervical dystonia.

Currently Botulinum Toxin is one of the most researched compounds known to mankind. It has over 60 recorded clinical applications including the treatment of wry neck, muscle spasm and pain. More recently exciting developments have occurred in the field of migraine prophylaxis and pain.

Currently Botox is licensed to treat the following conditions in the United Kingdom:-

Cervical dystonia – otherwise known as wry neck or torticollis causing severe muscle spasm in the neck

Strabismus – involuntary muscle spasm in the face

Unlicensed indications include the treatment of various muscle pain syndromes such as piriformis syndrome, spasticity, hyperhydrosis (sweating) and migraine.

Botox is thought to act by two distinct mechanisms. It has a direct pain killing effect (anti-nociceptive effect) as a result of blocking central transmission of pain impulses from the periphery to the brain. It also acts on muscle nerves resetting the level of contraction and thereby reducing muscle spasm.

Facts about Botox

Whilst the number of clinical indications for Botox has escalated dramatically over the last 5 years it is not a new drug or novel technique. It has been used cosmetically for around 15 years and indeed some of its beneficial effects in terms of pain alleviation were the result of a spin off from its use cosmetically. An example of this is the use of Botox in migraine prophylaxis where early indications of its potential benefit were derived from patients undergoing cosmetic treatment with Botox and noting a decrease in the frequency and severity of their migraine headaches.

The incidence of side effects or complications with Botox is incredibly small.

Unlike other analgesic preparations it does not cause systemic upset, central effects such as light headedness or failure of concentration, liver or kidney toxicity. There are no reported cases of allergy and improvements in manufacturing processes have resulted in an increase in the purity of the product and hence a decrease in tolerance secondary to the formation of antibodies on repeated injections.

Other complications are exclusively related to dosage and as such it is essential that your Botox injections are performed by an individual experienced and competent in the delivery of Botulinum Toxin injections. The commonest complication associated with excessive Botox injection is weakness in the affected muscle and this may for instance cause drooping of an eyelid underlying treatment for hyperactivity of the orbital muscles or neck muscle weakness in the treatment of cervical dystonia. Occasionally patients experience a flu like illness which is self limiting and occurs approximately 2 weeks after Botox injection.

The onset of action of Botox is approximately 2 weeks after injection.

Would my condition be suitable for Botox treatment?

Currently in the UK Botox has a product licence for the treatment of cervical dystonia and various ophthalmic conditions such as strabismus or blepharospasm.

It may be given however in a number of different conditions and studies are now emerging indicating its effectiveness in the treatment of:

Painful neck pain associated with muscle spasm

Piriformis syndrome

Complex regional pain syndrome

Lower back pain associated with muscle spasm

Migraine

Performed by – Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

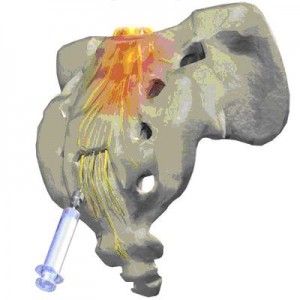

The piriformis muscle extends anatomically from the inner surface of the sacral bone and is inserted into the long bone of the leg, the femur. Occasionally the piriformis muscle may become irritable and goes into spasm and may be the cause of sciatic type pain in about 10% of cases of sciatica.

Features of the clinical presentation include buttock pain, referred pain to the thigh or frank sciatic pain, pain on sitting on the affected butt ock and difficulty climbing stairs or inclines.

There are no radiological investigations such as x-rays or scans which adequately demonstrate the presence or absence of a piriformis type syndrome and therefore the diagnosis is made predominantly on clinical grounds. Piriformis syndrome however may be a secondary feature of other spinal abnormalities such as wear and tear in the facet joints or a prolapsed intervertebral disc and therefore your clinician will probably organise an MRI scan of the lumbar spine to establish whether there are other primary changes responsible for the symptoms related to the piriformis muscle.

Treatment of piriformis syndrome consists initially of physiotherapy focusing on stretching the piriformis muscle. If radiological investigations such as scans demonstrate an abnormality in the lumbar spine these will have to be addressed as failure to address the primary pain generator will not adequately solve a piriformis problem.

If physiotherapy fails to alleviate the intense muscle spasm and associated referred pain, then targeted injection of the piriformis muscle is possible under x-ray or CT guidance and sedation. Initially injections into the piriformis muscle consist of preparations of local anaesthetic and a steroid however botulinum toxin has been very successfully injected into the muscle to alleviate spasm and there is reasonably good evidence based for the employment of this technique.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

Reason for Decompression surgery

The nerves within the spinal canal can become compressed over time due to thickening of ligament and overgrowth of bone. This compression within the spine is called stenosis. It will lead to back and leg pain and often pins/needles symptoms. These symptoms can be constant but are often associated with walking. Painkillers and epidural injections can be considered but the success rate is not always guaranteed and thus surgery becomes necessary.

Types of Decompression surgery

The main types of decompression are:

Microdiscectomy surgery

One or multiple level decompression

Decompression surgery that requires stabilisation or fusion surgery as well

Procedure

You will discuss the surgery with your surgeon both in clinic but also on the day of the procedure. The anaesthetist will also discuss the procedure with you. X-rays will be taken during surgery to ensure the correct nerves are being thoroughly decompressed. Afterwards you will start the recovery and rehabilitation phase with the nurses and physiotherapists on the ward. You should generally expect to leave hospital 1-3 days after the surgery.

Risks of surgery

The role of surgery is to take pressure off the nerves, giving them the best chance of recovery. Sometimes the benefit is immediate but also they can remain permanently damaged from the pre surgery pressure. The full outcome of relieving nerve pressure can take 12-18 months. There are some risks with this type of surgery.

Infection – The risk is less than 1% and you will be given antibiotics during and after surgery to reduce the chance.

Bleeding – There is always a small amount of blood lost during any surgery but the risk of requiring a blood transfusion is very small. At times we can collect your own blood and then give it back to you in theatre.

Recurrence – Thickened bone and ligaments are removed to take pressure off the nerves, but these can regrow over time. At times revision surgery is required and the chance is about 2-5%.

Dural Tear – The brain, spinal cord and nerves are bathed in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is housed in a sheath called the dura, which is as thin as tissue paper. There is a risk of puncturing this membrane which can lead to headache symptoms. These symptoms last for a few days and then settle, but very rarely further surgery to close the leak may be discussed.

Nerve Injury – During surgery the nerves are decompressed and manipulated and the implants are inserted very close to the nerves. This can result in damage, which is often temporary but can be permanent. This can lead to symptoms of ongoing pain, numbness or weakness in the leg. The chance of paralysis is possible but very rare with fusion surgery.

Cauda Equina syndrome – Both during and after surgery, a blood clot can put pressure on the nerves passing the operation area. These nerves pass the area to supply the bladder, bowel and sexual function nerves. If pressure is significant, this can lead to a loss of bladder/bowel and sexual function permanently but the risk of this approximately 1 in 5000.

Review / Follow-up from surgery

It is important patients follow the guidance of their surgeon and physiotherapist for the best rehabilitation following decompression surgery. It is vital patients perform regular exercises to prevent the back going into spasm. Patients will generally be discharged a few days after surgery and then see their GP or GP Practice nurse at 2 weeks for a review of the wound. They will then be followed up by their surgeon at 6-8 weeks post operatively.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

Reasons for Fusion surgery

This is a procedure that aims to join two or more vertebrae together. It is generally considered due to unstable or degenerate discs that stop functioning lead to pain. If all other avenues of treatment have been tried or considered, then your surgeon may discuss fusion surgery to improve back and leg symptoms.

Main Types of Fusion

Anterior lumbar fusion (ALIF) – Performed through an incision at the base of your abdomen Lateral lumbar fusion (XLIF or DLIF) – Performed through an incision through the side/flank of your abdomen Posterior lumbar fusion (PLIF, TLIF, MIDLIF) – Performed through an incision through your back.

Different conditions lend themselves to different types of fusion surgery and this will be discussed with your surgeon. Fusing 1 or 2 levels of the spine does not dramatically impact on patient’s movements or abilities with daily tasks and can lead to a big improvement of symptoms. The aim of surgery is to improve your level of pain, allowing for a more comfortable life.

Procedure

The surgeon and anaesthetist will discuss the procedure at length with you. It will take a few hours in theatre, where you will be carefully monitored and x-rays will be taken during the procedure to assist the surgeon. Afterwards you will start the recovery and rehabilitation phase with the nurses and physiotherapists on the ward. You should generally expect to leave hospital 2-5 days after the surgery.

Risks of Fusion surgery

The benefit of relieving pressure on the nerves can be immediate but sometimes takes months to recover. The bones will usually take 6-9 months to solidly fuse and thus back pain symptoms rarely improve in the early weeks/months. Although it is often successful surgery in improving symptoms, there are risks with the surgery.

Infection – Antibiotics are given in theatre and afterwards to reduce the chance of infection but it is still about 1%. This can usually be treated with a course of antibiotics but may require a further surgical procedure.

Bleeding – There is always a small amount of blood lost during any surgery but the risk of requiring a blood transfusion is very small. At times we can collect your own blood and then give it back to you in theatre.

Non union – We aim to join 2 bones together but there is a risk that the bones may not join up properly, called non union. If this occurs this can lead to ongoing pain and further repeat fusion surgery can be considered but carries higher risks. It is vital that you consider stopping smoking pre fusion surgery as this cuts down successful fusion rates by around 50%.

Dural Tear – The brain, spinal cord and nerves are bathed in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is housed in a sheath called the dura, which is as thin as tissue paper. There is a risk of puncturing this membrane which can lead to headache symptoms. These symptoms last for a few days and then settle, but very rarely further surgery to close the leak may be discussed.

Nerve Injury – During surgery the nerves are decompressed and manipulated and the implants are inserted very close to the nerves. This can result in damage, which is often temporary but can be permanent. This can lead to symptoms of ongoing pain, numbness or weakness in the leg. The chance of paralysis is possible but very rare with fusion surgery.

Cauda Equina syndrome – Both during and after surgery, a blood clot can put pressure on the nerves passing the operation area. These nerves pass the area to supply the bladder, bowel and sexual function nerves. If pressure is significant, this can lead to a loss of bladder/bowel and sexual function permanently but the risk of this approximately 1 in 5000.

Review / Follow-up from Fusion surgery

It is important patients follow the guidance of their surgeon and physiotherapist for the best rehabilitation following fusion surgery. It is vital patients perform regular exercises to prevent the back going into spasm. Patients will generally be discharged a few days after surgery and then see their GP or GP Practice nurse at 2 weeks for a review of the wound. They will then be followed up by their surgeon at 6-8 weeks post operatively.

Reasons for Fusion surgery

This is a procedure that aims to join two or more vertebrae together. It is generally considered due to unstable or degenerate discs that stop functioning lead to pain. If all other avenues of treatment have been tried or considered, then your surgeon may discuss fusion surgery to improve back and leg symptoms.

Main Types of Fusion

Anterior lumbar fusion (ALIF) – Performed through an incision at the base of your abdomen Lateral lumbar fusion (XLIF or DLIF) – Performed through an incision through the side/flank of your abdomen Posterior lumbar fusion (PLIF, TLIF, MIDLIF) – Performed through an incision through your back.

Different conditions lend themselves to different types of fusion surgery and this will be discussed with your surgeon. Fusing 1 or 2 levels of the spine does not dramatically impact on patient’s movements or abilities with daily tasks and can lead to a big improvement of symptoms. The aim of surgery is to improve your level of pain, allowing for a more comfortable life.

Procedure

The surgeon and anaesthetist will discuss the procedure at length with you. It will take a few hours in theatre, where you will be carefully monitored and x-rays will be taken during the procedure to assist the surgeon. Afterwards you will start the recovery and rehabilitation phase with the nurses and physiotherapists on the ward. You should generally expect to leave hospital 2-5 days after the surgery.

Risks of Fusion surgery

The benefit of relieving pressure on the nerves can be immediate but sometimes takes months to recover. The bones will usually take 6-9 months to solidly fuse and thus back pain symptoms rarely improve in the early weeks/months. Although it is often successful surgery in improving symptoms, there are risks with the surgery.

Infection – Antibiotics are given in theatre and afterwards to reduce the chance of infection but it is still about 1%. This can usually be treated with a course of antibiotics but may require a further surgical procedure.

Bleeding – There is always a small amount of blood lost during any surgery but the risk of requiring a blood transfusion is very small. At times we can collect your own blood and then give it back to you in theatre.

Non union – We aim to join 2 bones together but there is a risk that the bones may not join up properly, called non union. If this occurs this can lead to ongoing pain and further repeat fusion surgery can be considered but carries higher risks. It is vital that you consider stopping smoking pre fusion surgery as this cuts down successful fusion rates by around 50%.

Dural Tear – The brain, spinal cord and nerves are bathed in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is housed in a sheath called the dura, which is as thin as tissue paper. There is a risk of puncturing this membrane which can lead to headache symptoms. These symptoms last for a few days and then settle, but very rarely further surgery to close the leak may be discussed.

Nerve Injury – During surgery the nerves are decompressed and manipulated and the implants are inserted very close to the nerves. This can result in damage, which is often temporary but can be permanent. This can lead to symptoms of ongoing pain, numbness or weakness in the leg. The chance of paralysis is possible but very rare with fusion surgery.

Cauda Equina syndrome – Both during and after surgery, a blood clot can put pressure on the nerves passing the operation area. These nerves pass the area to supply the bladder, bowel and sexual function nerves. If pressure is significant, this can lead to a loss of bladder/bowel and sexual function permanently but the risk of this approximately 1 in 5000.

Review / Follow-up from Fusion surgery

It is important patients follow the guidance of their surgeon and physiotherapist for the best rehabilitation following fusion surgery. It is vital patients perform regular exercises to prevent the back going into spasm. Patients will generally be discharged a few days after surgery and then see their GP or GP Practice nurse at 2 weeks for a review of the wound. They will then be followed up by their surgeon at 6-8 weeks post operatively.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

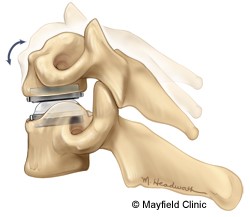

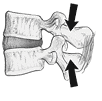

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is a surgical procedure performed to remove a herniated or degenerative disc (Fig. 1) in the cervical (neck) spine. The surgeon approaches the spine from the front, through the throat area. After the disc is removed, the vertebrae above and below the disc space are fused together. Your doctor may recommend a discectomy if physiotherapy or medication fails to relieve your neck or arm pain caused by inflamed and compressed spinal nerves. Patients typically go home within a few days; recovery time takes 4 to 6 weeks.

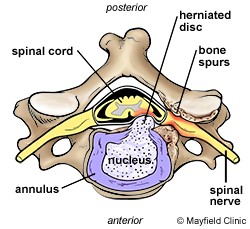

Millions of people suffer from pain in their necks or arms. A common cause of cervical pain is a rupture or herniation of one or more of the cervical discs. This happens when the annulus of the disc tears and the soft nucleus squeezes out. As a result, pressure is placed on the nerve root or the spinal cord and causes pain in the neck, shoulders, arms and sometimes the hands. Cervical disc herniations can occur as a result of ageing, wear and tear, or sudden stress like from an accident.

Most cases of cervical pain do not require surgery and are treated using non-surgical methods such as medications, physical therapy and/or bracing. However, if patients experience significant pain and weakness that does not improve, surgery may be necessary.

Surgical Technique

An anterior cervical discectomy (ACD) is the most common surgical procedure to treat damaged cervical discs. Its goal is to relieve pressure on the nerve roots or on the spinal cord by removing the ruptured disc. It is called anterior because the cervical spine is reached through a small incision in the front of the neck (anterior means front). During the surgery, the soft tissues of the neck are separated and the disc is removed. By moving aside the neck muscles, trachea, and oesophagus, the disc and bony vertebrae are accessed. In order to maintain the normal height of the disc space, the surgeon fills the space either with a cage filled with bone graft or a disc replacement. A bone graft is a small piece of bone, either taken from the patient’s body or from a bone bank. This cage fills the disc space and ideally will join or fuse the vertebrae together. This is called fusion.

It usually takes a few months for the vertebrae to completely fuse. In most cases, some instrumentation (such as plates or screws) may also be used to add stability to the spine.

After fusion you may notice some range of motion loss, but this varies according to neck mobility before surgery and the number of levels fused. If only one level is fused, you may have similar or even better range of motion than before surgery. If more than two levels are fused, you may notice limits in turning your head and looking up and down.

Motion-preserving artificial disc replacements have emerged as an alternative to fusion. Similar to knee replacement, the artificial disc is inserted into the damaged joint space and preserves motion, whereas fusion eliminates motion. Outcomes for artificial disc compared to ACDF (the gold standard) are similar, but long-term results of motion preservation and adjacent level disease are not yet proven. Talk with your surgeon about whether ACDF or artificial disc replacement is most appropriate for your specific case.

After Surgery

Patients will feel some pain after surgery, especially at the incision site. Pain medications are usually given to help control the pain. While tingling sensations or numbness is common, and should lessen over time, they should be reported to the doctor. Most patients are up and moving around within a few hours after surgery. In fact, this is encouraged in order to keep circulation normal and avoid blood clots.

However, most patients need to remain in the hospital, gradually increasing the amount of time they are up and walking, before they are discharged. Prior to discharge the doctor and physiotherapist will provide the patient with careful directions about activities that can be pursued and activities to be avoided. Often patients are encouraged to maintain a daily low-impact exercise program. Walking, and slowly increasing the distance each day, is the best exercise after this type of surgery.

Some discomfort is normal, but pain is a signal to slow down and rest. Keep in mind the amount of time it takes to return to normal activities is different for every patient.

Discomfort should decrease a little each day. Increases in energy and activity are signs that recovery is going well. Maintaining a healthy attitude, a well-balanced diet, and getting plenty of rest are also great ways to speed up recovery.

What are the risks?

No surgery is without risks. General complications of any surgery include bleeding, infection, blood clots (deep vein thrombosis), and reactions to anesthesia. If spinal fusion is done at the same time as a discectomy, there is a greater risk of complications. Specific complications related to ACDF may include:

Hoarseness and swallowing difficulties

In some cases, temporary hoarseness can occur. The recurrent laryngeal nerve, which innervates the vocal cords, is affected during surgery. It may take several months for this nerve to recover. In rare case (less than 1/250) hoarseness and swallowing problems may persist and need further treatment with an ear, nose and throat specialist.

Vertebrae failing to fuse

Among many reasons why vertebrae fail to fuse, common ones include smoking, osteoporosis, obesity, and malnutrition. Smoking is by far the greatest factor that can prevent fusion. Nicotine is a toxin that inhibits bone-growing cells. If you continue to smoke after your spinal surgery, you could undermine the fusion process.

Hardware fracture

Metal screws, rods, and plates used to stabilize the spine are called “hardware.†The hardware may move or break before your vertebrae are completely fused. If this occurs, a second surgery may be needed to fix or replace the hardware.

Bone graft migration

In rare cases (1 to 2%), the bone graft can move from the correct position between the vertebrae soon after surgery. This is more likely to occur if hardware (plates and screws) are not used to secure the bone graft. It’s also more likely to occur if multiple vertebral levels are fused. If this occurs, a second surgery may be necessary.

Transitional syndrome (adjacent-segment disease)

This syndrome occurs when the vertebrae above or below a fusion take on extra stress. The added stress can eventually degenerate the adjacent vertebrae and cause pain.

Nerve damage or persistent pain.

Any operation on the spine comes with the risk of damaging the nerves or spinal cord. Damage can cause numbness or even paralysis. However, the most common cause of persistent pain is nerve damage from the disc herniation itself. Some disc herniations may permanently damage a nerve making it unresponsive to decompressive surgery. Be sure to go into surgery with realistic expectations about your pain. Discuss your expectations with your doctor.

Infection

There is a small chance of wound infection. In very rare cases this can spread to the deep tissues and require further surgery to eradicate it. Signs of infection like swelling, redness or draining at the incision site, and fever should be checked out by the surgeon immediately.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

What is Spinal Stenosis?

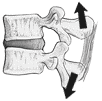

The spinal canal transmits a sheath which contains nerve rootlets bathed in fluid (CSF). The canal is bounded at the front by the verterbral bodies and intervertebral disc and at the back by bridges of bone (laminae) separated by a ligamentous membrane ( ligamentum flavum) and the facet joints.

As the disc degenerates with age it loses height and bulges backwards. This allows the ligamentum flavum to buckle inwards. Corresponding arthritic change in the facet joints causes them to enlarge and encroach upon the spinal canal. One or all of these changes can occur to cause a narrowing of the spinal canal and compression of the nerves. This is known as spinal stenosis.

What are the symptoms?

Classically the symptoms are of leg ache, fatigue, weakness, numbness and pins and needles that come on after standing or walking and progressively build up in intensity with time. Often the symptoms reverse on sitting or leaning forward but as the condition progresses they can become constant. Back pain may or may not be associated with spinal stenosis.

What treatment is there?

Painkillers: Often there is an inflammatory component to the pain so simple painkillers and anti-inflammatories may be beneficial in the early stages

Physiotherapy: In the early stages physiotherapy may be beneficial. The mechanism of benefit is not clear. My personal view is that building up the muscles that support the spine may prevent some of the spinal canal narrowing that occurs on standing or walking.

Epidural injection: again because of the inflammatory component a cortisone injection around the nerve roots may give relief of symptoms. If there is only temporary relief, then this still confirms the diagnosis and predicts a more successful outcome from surgery.

Facet joint injections: In the presence of back pain it is sometimes difficult to decide whether the leg ache is due to nerve compression or whether it is being referred down the leg from painful arthritic facet joints. It may be advisable to perform cortisone injections into the facet joints to try and work out whether your back pain is coming from this source.

If these non-operative treatments are failing or your symptoms are too severe to wait then surgery may be advised.

A decompression is also known as: laminectomy. It is performed under general anaesthetic and the surgery takes between 1 and 3 hours depending on the number of levels that need to be decompressed. This is a commonly performed surgical procedure which is performed from the back with the patient lying on their front. The skin and underlying muscles are cut to expose the back of the spine. Variable amounts of bone and ligament are removed until a big enough window is achieved to decompress the dural sac and nerve roots. You will be in hospital for 1-5 days after surgery. Postoperatively you will need physiotherapy and have exercises to do on your own. The wound will take 2 weeks to heal but absorbable sutures are used so there are no clips or sutures to remove. You should be able to return to work between 2 weeks to 2 months depending on your activity

What are the risks?

Immediate peri-operative risks

Anaesthetic risks: this procedure is performed under general anaesthesia and your anaesthetist will explain the risks to you.

Nerve damage: There is a small risk of nerve damage during this procedure. This may leave you with permanent numbness, weakness or pain in the area of the leg supplied by the nerve. The risk is less than1%.

Haemorrhage/Bowel damage: The front of the disc lies adjacent to the major abdominal blood vessels and contents. There have been reported instances of fatal complications arising from damage to these structures. This is very rare. This risk would only be present if a discectomy is performed at the same time as the decompression.

Cauda Equina Syndrome: If there is significant post-operative bleeding then the central spinal canal can become included with severe loss of function of the bowel and bladder and lower limbs which can be permanent. This complication is rare.

Dural tear: In spinal stenosis the lining of the nerve roots (dura) can become adherent to the surrounding tissues and can be torn. This leads to a fluid leak which can cause headaches and necessitate compulsory flat bed rest for 2 days. The fluid leak can often obscure vision and prevent the safe completion of surgery. A simple tear may be repaired but large tears have to be packed off.

Usually the leak seals itself off and routine mobilisation can follow but occasionally the leak can persist and necessitate a return to theatre to have the leak closed. The risk is 1-10%.

Infection: Infection following decompressive surgery is less common than after other types of surgery but infection in the spine can be very serious necessitating further major surgery and long term antibiotics. Infection carries the risk of nerve damage and meningitis.

Medium term risks

Failure to relieve symptoms. Sometimes the nerve damage may be to long standing to be reversible by decompression, It is the reversible symptomwhich respond best to surgery.

Back pain: The effect of decompressive surgery on the back pain component of spinal stenosis is unpredictable. Studies would suggest that in 50% of cases back pain will also be helped by the procedure but there is a 10% chance that the effect of surgery will worsen back pain or cause some new back pain. Usually this is not bad enough to warrant further surgery.

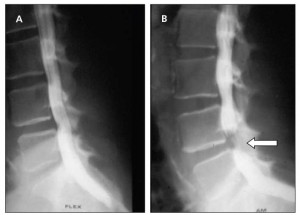

In certain circumstances it may be felt that your scan and xrays demonstrate sufficient instability to suspect an increased risk of post-operative back pain or recurrence of symptoms. In this case and additional procedure may be advocated at the time of surgery to stabilise the spine ( see Interspinous stabilisation and spinal fusion)

Long term risks

Nerve root scarring: It is thought that the trauma of surgery may induce scarring around the nerve root following decompression. This can cause the nerve root to become stuck down and cause pain. This is a very difficult problem to treat and may necessitate steroid injections or rarely further surgery to release the nerve.

Recurrent symptoms: decompressive surgery does not prevent further deterioration of your spine and symptoms can recur at the same level or other levels in the spine. This may necessitate further procedures.

QUESTIONS

This document is intended to cover the most significant risks and commonly asked questions. If you have further questions please contact your surgeon’s secretary.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Sarmad Kazzaz Mark Thomas Adam Way

What is a disc?

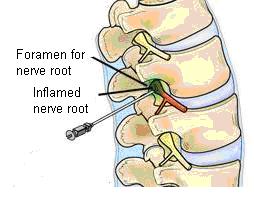

The intervertebral disc is a ring of fibrous tissue that lies between the vertebral bodies in the spine. It consists of a tough outer ring with a jelly-like centre. The disc normally absorbs water and acts as a shock absorber as well as providing stability to the spinal column. With age the lowest lumbar discs degenerate and can become less effective at their job. The lack of support is thought to cause back pain by straining the surrounding joints, ligaments and muscles. The disc may cause leg pain by compressing or irritating the adjacent nerve.

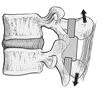

What is a disc prolapse?

Also known as: slipped disc, prolapsed interverterbral disc, disc herniation

Sometimes the tough outer ring of the disc tears and this allows the softer centre escape. If this material travels backwards it can compress the nerve root and cause leg pain i.e. sciatica. The pain is rarely due to physical compression alone and it is the chemicals released with this process that inflame the nerve root. This is why your doctor may prescribe anti-inflammatory medication. The pressure on the nerve may in addition to pain cause loss of function of the nerve i.e. numbness or weakness.

The majority of patients with disc prolapses will find that their pain will resolve spontaneously over a period of six weeks. They may require painkillers, anti-inflammatory medication or anti-inflammatory injections to help with their pain during this period. Numbness and weakness will also improve in the majority of cases but over a longer period of time. However, the recovery of numbness and weakness cannot be influenced by surgery.

What treatment is there?

Simple rest, painkillers and anti-inflammatories should be tried in the first six weeks. Try to keep mobile.

The role of physiotherapy, chiropractic manipulation and osteopathy in the acute stages is controversial but may help.

If your symptoms have not improved after six weeks your doctor will refer you to a spinal specialist. Depending on your symptoms consideration will be given to performing an epidural injection. These injections can take 2 to 4 weeks to work.

If these non-operative treatments are failing or your symptoms are too severe to wait then surgery may be advised.

Surgery is intended to relieve the leg pain arising from nerve root compression. The effect of surgery on back pain is unpredictable and is rarely the primary reason for surgery

What is a Discectomy?

The procedure is also known as a microdiscectomy. It is performed under general anaesthesia from the back with the patient lying on their front or side. The skin and underlying muscles are cut to expose the back of the spine. Small amounts of bone and ligament are removed until a big enough window is achieved to safely pull the nerve root to one side. The prolapsed material is then removed. Any loose fragments in the disc space are also removed. The amount of material usually represents about 20% of the disc. The rest of the disc is left in place. Nothing is placed in the disc to fill the space. The nerve is then replaced in its proper position. You will be in hospital for between 1 and 3 days and will then need physiotherapy together with exercises to do at home. The wound takes about 2 weeks to heal and you should be able to return to work between 2 -8 weeks after surgery depending on your activity

What are the risks?

Studies would suggest that in the long term (3 years) the end functional result flowing a disc prolapse is the same whether an operation has been performed or not. A successful operation is associated with an earlier achievement of this end result. There is, however, a small but definitive risk of complications some of which can be very serious. Therefore your surgeon will not generally recommend surgery without offering a non operative alternative.

Anaesthetic risks: this procedure is performed under general anaesthesia and your anaesthetist will explain the risks to you.

Nerve damage: There is a small risk of nerve damage during this procedure. This may leave you with permanent numbness, weakness or pain in the area of the leg supplied by the nerve. The risk is 1%.

Haemorrhage/Bowel damage: The front of the disc lies adjacent to the major abdominal blood vessels and contents. There have been reported instances of fatal complications arising from damage to these structures. This is very rare.

Cauda Equina Syndrome: If there is significant post-operative bleeding then the central spinal canal can become included with severe loss of function of the bowel and bladder and lower limbs which can be permanent. This complication is rare.

Dural tear: Sometimes during surgery the lining of the nerve roots ( dura) can be torn. This leads to a fluid leak which can cause headaches and necessitate compulsory flat bed rest for 2 days. Usually the leak seals itself off and routine mobilisation can follow but occasionally the leak can persist and necessitate a return to theatre to have the leak closed. The risk is 1%.

Infection: Infection following discectomy surgery is less common than after other types of surgery but infection in the disc space can be very serious necessitating further major surgery and long term antibiotics. Infection carries the risk of nerve damage and meningitis.

Medium Term Risks

Recurrent disc prolapse: As the whole disc has not been removed further material can dislodge at a later date. This is fairly uncommon.

Recurrent pain: It is not unusual for some of the symptoms of sciatica to return a few weeks after the procedure. This is probably due to the swelling and bleeding around the nerve root following surgery. If this does not settle with anti-inflammatory medication an epidural injection may be required.

Back pain: the cut muscles take some time to recover and the first two months following surgery may be associated with discomfort following prolonged activity and sitting.

Long Term Risks

Nerve root scarring: It is thought that the trauma of surgery may induce scarring around the nerve root following discectomy. This can cause the nerve root to become stuck down and cause pain. This is a very difficult problem to treat and may necessitate steroid injections or rarely further surgery to release the nerve.

Back Pain: This is not necessarily related to surgery. A damaged disc does not repair itself and will not function as normal. By building up the supporting muscles around the spine back pain can be prevented (core stability) but occasionally, despite this, back pain can be a problem. There is no way to predict this at the time of the discectomy with certainty but occasionally your surgeon may recommend additional procedures to try and prevent this problem occurring.

Questions?

This document is intended to cover the most significant risks and commonly asked questions. If you have any further questions then please contact your surgeon’s secretary.

Performed by – Sri Chatakondu Mark Thomas Adam Way

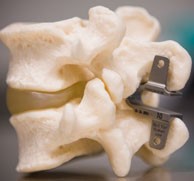

What is interspinous stabilisation?

This is a procedure that is carried out as an adjunct to a lumbar spinal decompression or discectomy. Sometimes the surgeon may feel that there is an element of instability associated with the degeneration causing spinal stenosis. In this circumstance the patient might complain of significant back pain as well as leg pain. There may also be a concern that the narrowing around the nerves may recur at a later date as the disc degenerates further. A further concern may be that a very large disc prolapse will lead to significant back pain in the future despite successful initial surgery.

|

One way to tackle this excessive motion would be by performing a spinal fusion. This is often a much more involved procedure than a straight forward decompression or discectomy and with a higher rate of complications and a slower recovery. As the incidence of the problems highlighted above is low; it would be unreasonable to perform a spinal fusion in everyone at the outset.

A variety of implants have been designed to try and achieve a middle ground. They are simple to put in and do not require much more muscle dissection than a straightforward decompression. The recovery from this operation is therefore about the same as are the risks.

The commonest devices are the COFLEX, WALLIS LIGAMENT and DIAM

They all sit in the interspinous space but have different attachment methods and characteristics.

|

What are the advantages?

All of these devices are simple to put in and do not require much more tissue damage than the primary procedure. The recovery and risks are therefore similar to the primary procedure. If the device is successful in preventing future problems then a much more complex operation will have been avoided.

Another advantage of these implants is that they do not interefere with the ability to perform a more complex procedure at a later date should this be necessary.

What are the disadvantages?

The advantages are theoretical. In theory these devices should provide some extra stability to the decompressed lumbar spine level and laboratory studies on models would support this. However, to prove an effect in actual patients is much more difficult as no two patients are the same. In the absence of randomised clinical trials these devices must be regarded as experimental.

What are the risks?

The risks are the same as for the index procedure (lumbar decompression or discectomy) but in particular.

Infection: whenever a foreign material is inserted into the body the risk of infection is raised. This is still a low risk.

Dislodgement of prosthesis: As with any implant the device can become dislodged or loose. This may cause pain. A particular possibility with interspinous devices is fracture of the spinous process. This seems to be rare with the devices mentioned above.

Questions?

This document is intended to cover the most significant risks and commonly asked questions. If you have any further questions then please contact your surgeon’s secretary.